Impastato: The fighting, the murder, the inquiry, the misdirection, and the sender’s indictment.

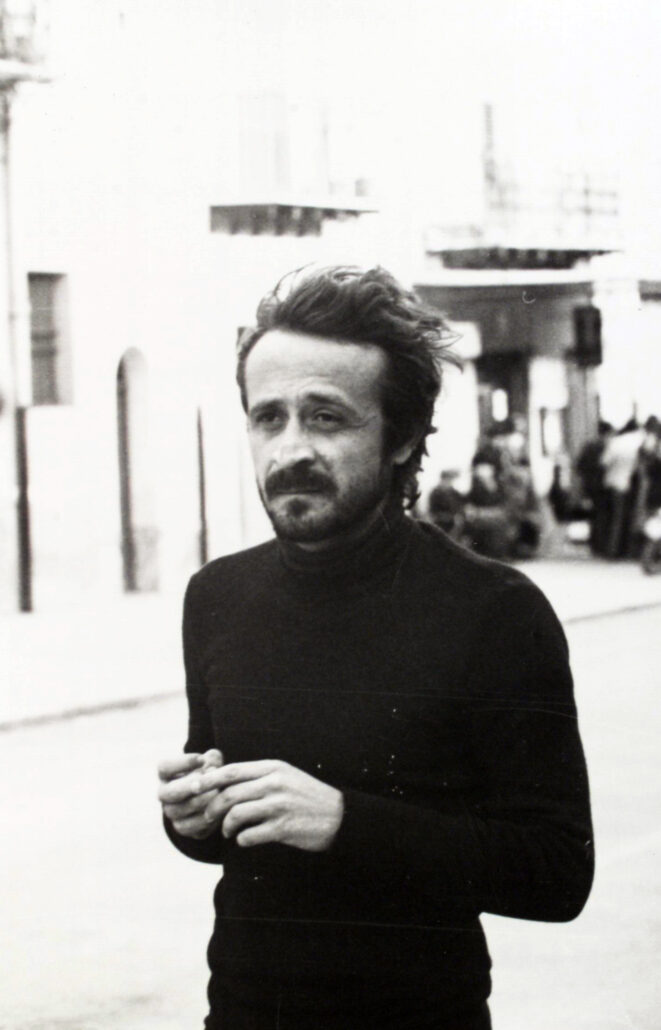

Giuseppe (Peppino) Impastato was born in Cinisi, within Palermo’s province, on January 5th, 1948, to a mafia family: Luigi, his father, was already exiled during the fascist rule, while his uncle and close relatives were mafiosos. The most important of them was Cesare Manzella, Luigi’s brother-in-law and major mafia boss of Cinisi. He was murdered by car bombing in 1963, while Peppino was still a child. After witnessing his uncle’s assassination, Peppino openly spoke out against the mafia, bringing his father to disown him and banish him from the family house, and leading him to start a political and cultural fight against the mafia.

In 1965, Peppino established the newspaper “L’idea socialista” [The socialist idea] and joined the PSIUP (Italian Socialist Party for the Proletarian Union). From 1968 onwards, he joined the militants of the “new left.” Peppino and his comrades fought for the rights of the farmers who lost their homes during the construction of the Cinisi airport’s third lane, for the rights of the construction workers and for the rights of the unemployed. In 1975, he started the “Music and Culture” group, taking part in various cultural activities (Movie festivals, Music concerts, Theatre plays and Political debates); In 1977, Peppino founded “Radio Aut” (From the Latin word for “Alternative”), a free and self-funded radio station, through which he reported the murders and deals of the mafiosos in Cinisi and Terrasini, with a particular focus on Gaetano Badalamenti, who had a critical role in the international drug trade. After that, the radio station had a time slot called “Onda Pazza” (Insane Wave), a satirical program which poked fun at mafia bosses and politicians.

In 1978, Peppino became a candidate for the Proletarian Democracy party in the town’s elections.

He was murdered the night between May 8th and 9th, halfway through his political campaign: his body was laid out on a railway and blown up with five kilograms of TNT placed under it. The same day his remains were found, Aldo Moro’s corpse was discovered in Rome. The news of his death unfortunately ended up overshadowing the coverage of Peppino’s death, relegating him to a footnote in history for the years to come.

The judiciary and the press all commented on Peppino’s death as a terrorist attack that killed the perpetrator. In a phonogram, the head prosecutor wrote: “Terrorist attack against transport security with a dynamite explosive. Around 030-100 hours on 05/09/1978, currently unknown but possibly identified the perpetrator Giuseppe Impastato on location, KM 30+180 of the Trapani-Palermo Road, placing an explosive charge which, exploding, killed the perpetrator.” The discovery of a letter, written months ahead of his death, completed the picture for many: the attacker was suicidal. Peppino’s comrades were investigated as co-perpetrators, and the houses of both Peppino’s mother and aunt were searched, together with those of his comrades. The mafia bosses’ houses and caves were not searched, despite the investigation revealing that the explosive charge was the same used in cave mining, which were notoriously owned by the above mentioned mafia bosses. Shortly after his death a paper was published in Cinisi, claiming that the mafia was responsible for the murder. Soon, another was paper published in Palermo claiming “Peppino has been killed by the Mafia.” Around one thousand people took part in Peppino’s funeral, many coming from Palermo and other nearby towns and cities. On the same day, the University of Palermo’s School of Architecture, with the help of a retired legal medicine teacher, Del Carpio, dismantled the terrorist attack and suicidal allegations towards Peppino.

On May 11th, in Cinisi, as the electoral campaign in which Peppino took part in drew to a close, a political rally that Peppino and a Proletarian Democracy party head were supposed to lead was instead led by Umberto Santino, the founder of Impastato Center, during which he accused Cinisi’s mafia, with a particular focus on Gaetano Badalamenti, as the Peppino’s murder. During this time, Peppino’s comrades got hold his remains, discovering that he was attacked and murdered. On May 16th, Peppino’s mother, Felicia Bartolotta, and his brother Giovanni, sent a notice to Palermo’s district attorney accusing Badalamenti of being the instigator of Peppino’s murder. Cinisi’s residents voted for him posthumously, electing him to the Town’s council thanks to his brother and mother, who publicly rejected their mafia relations, and his comrades as well as the Impastato Center’s efforts. In July 1978, a document detailing ten years of fighting against the Mafia was published, and the investigation about those responsible for Peppino’s murder re-opened.

In May 1979, for the first anniversary of Peppino’s murder, the Center, with the support of the Proletarian Democracy party, organized the first National Rally against the Mafia in Italian History, with over two thousand participants.

In May 1984, Palermo’s court, based on councilor Rocco Chinnici (who had started his own work against the mafia, and was murdered in July 1983)’s instructions, published a statement (signed by the instructor councilor Antonino Caponnetto) in which they recognized the mafia as the instigators of Peppino’s murder, but attributed it to unknowns.

The Impastato Center published, in 1986, the life story of Peppino’s mother, entitled “La mafia in casa mia” (The mafia in my own home), and the dossier “Notissimi Ignoti” (The well-known unknowns), in which Gaetano Badalamenti was accused of murdering. Meanwhile, Badalamenti had been sentenced to forty-five years in prison for his connections to international drug trade by New York’s court, as part of the “Pizza Connection” operation.

Peppino’s mother later revealed a moment of their lives: her husband, Luigi, after a meeting he had with Badalamenti, undergoing particularly harsh accusation written in Peppino’s paper, traveled to the US. During these travels he would tell one of his American relatives “If they want Peppino they’ll have to go through me.” He allegedly died in a car crash on September 19th, 1977.

In January 1988, Badalamenti was summoned by Palermo’s Court, and in May 1992, the case was filed, confirming the mafia’s role in the murder but excluding the possibility of finding exact perpetrators.

In May 1994 the Impastato Center sent a request to reopen the case, helped by popular demand, which led to the interrogation of justice collaborator Salvatore Palazzolo, who, in June 1996, directly stated Badalamenti sent the order to assassinate Peppino, together with his right-hand man Vito Palazzolo. The investigations were officially reopened. In November 1997, the court ordered the capture of Gaetano Badalamenti, and in March 1999 Vito Palazzolo was convicted as an accomplice to murder.

Thanks to Peppino’s family, the Impastato Center, the Rifondazione Comunista party, Cinisi’s town hall and the Order of Journalists, on November 23rd, 1999, Badalamenti requested a speedy trial. On January 26th, 2000, Vito Palazzolo asked for an abbreviated procedure, while Badalamenti received a regular audience via video call, as he was jailed in New York for his international drug trade discovered during the “Pizza connection” operation. On December 6th 2000, the court finds a relation between the judiciary and the red herring regarding Peppino’s murder, which was then published in the book “Peppino Impastato: Anatomia di un Depistaggio” [Peppino Impastato: Anatomy of a Red Herring].

In September 2000, the movie “I Cento Passi” (The Hundred Steps) came out, letting the wider public know about Peppino’s story.

On March 5th 2001, Assise’s Court sentenced Vito Palazzolo to thirty years in prison. On April 11th 2002, Gaetano Badalamenti was sentenced to life in prison. Both of them died in prison years later.

On December 7th 2004, Felicia Bartolotta, Peppino’s mother, passed away.

In 2011, Badalamenti’s house was reclaimed by Casa Memoria “Felicia e Peppino Impastato” and the “Peppino Impastato” Association. Also in 2011, Palermo’s prosecution re-opened their investigations on the red herring.

In April 2012, another edition of “Peppino Impastato: Anatomy of a Red Herring” was published.

Translated by Giuseppe Palazzolo